It was late in 2015. Maybe November. Maybe December.

I had been in Punjab for three or so months by then, reporting for Ear To The Ground. By then, I had written on the farm crisis in the state; on deindustrialisation in its cities; and I had begun grasping the Akali Dal’s stranglehold over both economic activity and religious bodies in the state. What I did not know, however, was how all this decay and disarray was affecting the people.

And so, one evening while in Chandigarh, I called Desraj Kali. Annie Zaidi had given me his number on hearing I was heading to Punjab. I had meant to meet him — writers/poets/artists have a window to the psyche of the state — and now, it felt like I was ready. And so, I call. Introduce myself. Outline what I have seen. And pose my question: “I see all these troubles that people are in. What I don’t understand is how people are responding to these crises.”

Kali: “Oh oh! Iske liye to rum peena padega (for this, we will need rum)!”

And so, a few days later, I get to Jallandhar. It’s late in the evening when the bus drops me there. I dump my bags and follow Kali’s directions to his office. It’s about eight at night. It’s nippy. I take a shared auto-rickshaw and get dropped about ten minutes later on a poorly lit but central thoroughfare in Jallandhar. (The detail is granular here, I know. That is because Kali is gone and I am trying to put down what I remember before these precious memories fade).

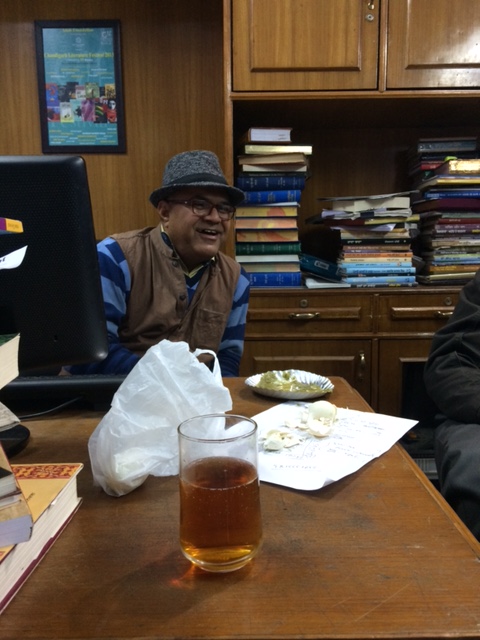

I call Kali. He comes out — a bald man of average height running to pudginess — and says he has a couple of friends at his office and that he has told them he has an interview. And so, can we just drop in at his office for a couple of minutes and then we will go to my hotel and we can chat aaram se (at ease). Sure, I say. We reach Kali’s office only for me to find that it is actually a small shop, complete with a rolling shutter, that he has converted into a work-space. Two computers. Shelves crammed with books and papers. A bottle of rum on the table to the left. Some boiled eggs on a sheet of paper. And three guys sitting there. The first, a doctor. The second, a reporter who, as I find, is fond of talking about the stories he has done (I saw myself in him). And the third, a businessman. The conversation is ordinary. The businessman bitches about NREGA — workers are spoilt now, etc etc. The Doctor, who is left leaning, defends it. The reporter tells me about the stories he has done.

Ten-fifteen minutes of this. And then Kali makes his excuses, drags me out, we start walking to his bike, and then he says: “Yeh sab merey agley upanyaas ke patr hain (all of them are characters in my next novel).” In other words, he had modeled three characters in his next novel on his friends and, every time he felt stuck, he would call them over for drinks and then pose an innocent question (A la “What do you think of NREGA?”) and use the resulting chatter to move the story forward.

Here is a mischievous mind, I think, which doesn’t take a lot of things very seriously. A very good trait. And so, we ride back to the hotel with me asking Kali if I too might end up as a patr in a future novel. Maybe, he says.

We stop at a booze shop to buy rum — the hotel will charge a lot and give only one or two pegs, says Kali, much better to just buy the bottle outside — and then we get to the hotel. We settle down. I pose my question again. And, well, I have written about the epiphany-laced chat that followed in an article that followed.

I remember listening agog — each of these factoids entirely new to me — wondering where he was going.

That night, he drew a link between precarity, insecurity and this turn towards the supernatural.

It was a revelatory moment. The first step towards the realisation that people respond to under-development not by seeking democratic recourse but in more complicated ways — by heading deeper into religion for solace; or trying to land a better deal through identity politics. As Kali said about Punjabi pop videos: “The songs have guns, big houses, open jeeps, Royal Enfields. Even as people struggle, caste ka ghamand liye ghoom rahein hain (They are drawing arrogance from their caste).”

In some months, I would leave Punjab for Tamil Nadu — and then find the same pattern there as well.

That chat with Kali ended. Maybe later that night — or a subsequent night after an equally long rum-laced chat — he said “chalo, main aapko apni ma se milata hoon (Come. I will introduce you to my mother).” We don’t go to his house, though. We walk out of the hotel into the lanes of a shuttered market. There, a woman in her fifties is cooking and selling parathas. She cycles over here every night from a village outside the city, says Kali, sets up her stove, and makes parathas for all the workmen heading home after their shift.

He accosted a passerby heading home — a staffer in some hotel, i think — and here is a snap of them eating together.

He had called her “meri ma”. In the hotel, I remember him charming the room service staff. Another night, he took me for a ride on his motorcycle and pointed out an intersection where sex workers often stood. Some of them farm widows with kids to bring up. “Sometimes I come and talk to them. If they need it, I give them some money.” He listened to them, heard them talk about their lives, created a map of modern Punjab through the hundreds, if not thousands, of stories he had heard. All of it coming together as an acute assessment of our times. As he said on that bike: “Yeh phoohadpan ka daur hain (this is a time of immature stupidity).”

Even the Akali Dal MLA I met was because of Kali. The politician too had unburdened himself before Kali. That capacity to care is my most abiding impression of Kali.

The Punjab stint ended. I moved to Tamil Nadu. And then, Bihar, Gujarat, and Delhi. Moved next to Bangalore. Got busy with work again. And, just as I had meant to with Debjeet Sarangi, I aimed to meet Kali whenever next in Punjab. With both of them, I assumed I had time. But gentle, strapping Debjeet fell to Covid. And Kali has now fallen to liver disease. And life stands further impoverished.

In the days to come, others will write better accounts of Kali. His body of work as a dalit writer. His friends will have known him far better than me — and so, I will keep an eye out for their elegies as well. But even in the fleeting hours we spent together, Kali left a mark!

One more exemplar on how to live. I will miss him.

PS: Here, an obituary in Tribune.

PS: And here, an obit in The Wire. “Hailing from the Dalit heartland of Punjab, the Doaba region, Kali’s work was influenced by the teachings of Sufi saints who thronged the villages and deserts of undivided rural Punjab, and iconic Dalit writers Lal Singh Dil and Sant Gulab Das. The originality in his work brought a new turn in Punjabi story writing. Kali explored anti-caste struggles, culture, tradition and literature in the form of novels and short stories. He also presented research papers in renowned universities.”

PS: Here is Annie remembering Kali. “He was unabashed in his expression of affection and sometimes when he called, he would admit that he was drunk and that he was ringing up all the people he loved.”

Leave a comment