One of my resolutions last year was to travel more. Not an easy thing to do given the demands of work and life but still, to sneak out for little breaks whenever I can.

This objective was met last year when, while researching for the oil palm report, I paused briefly at Kaziranga. And now, drumroll, that objective has been met in 2025 as well. I went to Great Nicobar.

I had been meaning to go to this island for a long time. In that first trip to the Andamans, I had entertained inchoate (and ultimately impossible) plans of seeing the reticulated pythons of Great Nicobar. Impossible, as I said, because I had no sense of distance or shipping schedule. There was only the mind going agog at the thought of going to an unfamiliar biogeographic zone and hatching fanciful plans.

That was in 2004. Ten years passed before I went back to the islands. That was another of our end of the year cycle rides. We had started at Wandoor and pedalled to Diglipur in the north.

Along the way, there had been some snorkelling, some diving, and some more biodiversity spotting. What I remember most from that trip, however, were the banded sea kraits coming up to rest every evening at the Wandoor beach. It had been every bit as extraordinary as an arribada. The sun would dip, evening darkening into dusk, and one started to see kraits everywhere. A rope-like curve of alternating white and black bands being pushed onto the beach by a wave — krait! That white and black line on a beached tree trunk — krait! Those lines moving up the sand to the grasses and plants growing higher up on the beach — kraits! In a fifty metre stretch, as I remember now, I saw as many as fifteen or twenty of these! There were other water snakes we saw, there was a shark we saw, but it is the kraits I remember most. Their arrival was an ancient rite that had somehow persisted into modern times. Later on during that trip, closer to Diglipur, we saw a turtle — I forget which species — laying eggs as well. Nicobar, however, stayed elusive.

Ten more years passed. About two years ago, the Great Nicobar transhipment port project made its way onto my to-do list. I reported in bits and pieces — during one trip to Delhi, another to Mumbai, and a third to Port Blair — for a report that is just out. What came with it, however, was a rising urgency to see the island while it’s still pristine.

I have only seen landscapes with varying degrees of degradation and fragmentation. Periyar is sullied by the dam in its middle. Corbett has its teak plantations, to say nothing of mass tourism. In each of these, one wonders how the place would have looked before modern man — or before man entirely.

Great Nicobar is different. Given its great distance from the mainland, it has barely any trade relations with the world outside. It exports little. Its population is low enough to stay within the island’s carrying capacity. In all, one could stand here — on its beaches or in its forests — and see an ecosystem yet untouched by modernity and enriched, thanks to isolation, with a strikingly endemic assemblage of species closer in origin to those in Indonesia than anything in India. The Retic is one instance.

More urgently, the island — to borrow from Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s Friction — is also on the cusp of going from tropical wilderness to a resource frontier no different from the mining boomtowns like Koira, with expectations of modernity, speculators, get-rich-quick mindsets, and large-scale plunder. If one has to see the place, it’s now.

And so, that is what I did towards the end of January. I filed my report — and in this journalistic interregnum where one report is getting edited but work on the next is yet to start — I took the ship to Campbell Bay, the administrative centre of Great Nicobar.

Here is what I saw. Biodiversity, first.

In birds, crimson sunbirds on the first morning on the island.

On the second day, open billed stork, purple heron, asian glossy starlings, common mynahs, pied imperial pigeons, yellow wagtail, white-breasted waterhen, blacknaped oriole, parakeets, andaman green pigeon, and more crimson sunbirds.

In subsequent days, a white-bellied sea eagle and an emerald dove as well. This list is also on ebird.

I am a relative neophyte here. I had to photograph these birds, jot down the names uttered by the guide in my phone, and then compare with the bird guide later in the day. Had TR Shankar Raman tagged along that day, I can only imagine how many more species he would have spotted. Still, one lives and learns. .

I also saw a nest of the Nicobar megapode. I have read about these. Perhaps for the first time in Douglas Adams’ Last Chance To See when he goes to Komodo. He sits near a mound and tries to guess — or write a program that could compute — how long it would have taken the bird, using only its feet, to scrape together a mound of sand over a metre across and almost as high. I did not see the bird itself. But no matter. We travel not to see birds/animals but to see signs of their presence and to feel relieved that their ecosystems are intact.

That is how it would have felt on seeing the megapode’s nest if not for the port which will take over this part of GNI. There is some blithe talk about shifting the megapodes to another island, about creating wildlife management plans, but wild birds/animals get traumatised (even die) in such exercises. Modern India has a real habit of replacing real conservation with paper conservation — wildlife management plans in lieu of trees/biota — and this is just the latest instance.

I also saw Nicobar macaques. Maybe 30 of them. This post starts with a snap of an individual from the very first troop I saw. And I saw three Nicobar squirrels.

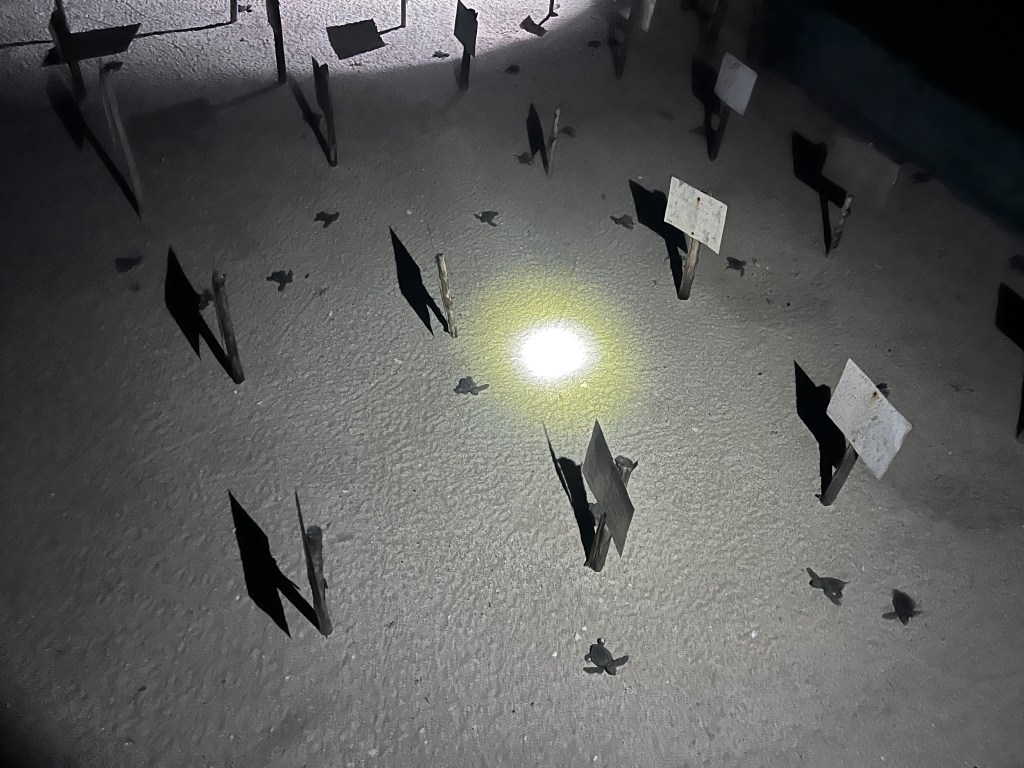

I didn’t get to see the famed saltwater crocodiles. Most probably live higher up in the marshes or on the other side of the island, away from humans. What I did see, however, were turtles. On the second night in the island, I was at Anderson beach, looking at the Milky Way and wondering if more turtles would turn up that night. The nesting season is coming to an end and so, one is never quite sure. It was one of those days when nature shows she calls the shots. An Olive Ridley had laid eggs and just before I reached. Another landed just after I left. But while I was there, one batch of Olive Ridley eggs hatched. There was a sudden exclamation from the forest guard who had walked over to the hatchery. And lo, little Olive Ridleys were walking around, each small enough to fit in a child’s palm, purposefully moving towards the sea.

The locals hired as forest guards were magnificent, doing their work with sincerity and love for the turtles. I had seen one shift eggs (those laid by the Olive Ridley which reached Anderson just before me) to the hatchery just after I reached. This is done to ensure dogs and, sometimes, monitor lizards, don’t eat the eggs. And now, I got to see them gently lift these fledgelings and put them in a box after counting. In the morning, they would be released into the sea.

One saw these, heard their loud scrambling inside the container, and felt rapture and pain. What does life hold for these little things that unthinkingly obey ancient instinct in a fast-changing world? Go well, one thinks. And hopes, so desperately, that they stay safe and live long.

Two days later, this scene was repeated. This time at Galathea Bay where I saw three leatherbacks, three or four leatherback hatchlings, and a small turtle — photography is banned on the beach and so I do not yet know if it was an olive ridley, a hawksbill, or a green. All are known to nest on Galathea. All I know is, compared to the leatherbacks, it was puny. After seeing the leatherbacks, one almost felt a sense of shock at how small it was.

Galathea was distressing. It was the usual shitshow. Folks walked up the beach while casually flicking needlessly powerful torch lights everywhere, even onto the sea. They stood around a turtle straining to dig a hole with her flippers to lay eggs — giving birth, basically — taking photos, using flashes and torches, taking selfies, what have you. Especially stressed turtles have been known to return to the sea without laying eggs. And so, I snapped at a few tourists, each of whom retreated but within two minutes, impelled by people’s modern need to constantly mythologise themselves through selfies, were back again. Another handful were touching its carapace and praying. How can something be simultaneously holy and undeserving of consideration? Yet other visitors, as I later heard, have also used torches to stop turtles from returning to the sea. Similar processes, incidentally, have also resulted in Banded Sea Kraits no longer being seen at Wandoor. I had gone there while in Port Blair. Not one snake in sight. The number of tourists had risen — and harassment of the snakes had climbed in sync. I do not know if the kraits relocated to another beach or, unable to shift to another location, died out.

This country truly doesn’t deserve its biodiversity.

Those were the major spottings. I didn’t see the retics. But that is nature for you. One sees birds/animals when they decide to present themselves. The most one can do is visit often and wait a while.

Another aspect from the trip stands out for me. The tsunami had struck the islands just as I left in 2004. I remember those days, shipping water purification tablets from Delhi, talking to Samir Acharya a week after the tsunami and hearing him say they had lived off cucumber sandwiches for a week. I remember too Khot’s photograph for Indian Express. And then, another ten years later, phone interviews with Nicobarese, asking about post-tsunami rehabilitation. Not to mention books like Pankaj Sekhsaria’s The Last Wave.

In that sense, I thought I understood better than most the effects of the tsunami. Not quite. Visiting the island brought those days home. Driving on the north south road, one sees open patches with only grasses and palms — a hard contrast from the lush forests on, say, the other side of the road. That is how far the sea had come in — as high as a coconut tree, multiple people said — leaving the land saline and fallow. One goes to a beach — say Vijay Nagar or Anderson — and feels nonplussed seeing concrete structures on the beach. At Anderson, one sees a water tank. It used to stand about 400 metres inland, as locals told me, with a road running in front of it, and beyond it, the settlement with homes, shops and whatnot. And beyond that, the sea.

Go now to the beach and you will see waves slapping the water tank. Everything in front of it is gone.

Even more haunting is Vijay Nagar. This is where Khot had taken his now famous photo. The structure below used to be the school — from 8th to 12 grade. “Many studied here and went on to join the government,” a local elder told me. Like the tank, it stood well behind the settlement and the coastal road. Look at it now.

One looks inside and gasps. That is a blackboard. One looks too at these pillars and grasps, so easily, how the school must have looked. Classrooms with a veranda, which must have looked out towards the settlement, running along their length. I don’t know if anything about the tsunami has shook me as much as this blackboard. That is how it is. We are inured to large numbers. Something smaller, however, will wreck our equilibrium. We can be affected only by what our brains can grasp and comprehend.

One sees such buildings, hears locals talk about that day, and thinks about the trauma that this hard-bitten population of Great Nicobar carries with it. Later yet, I saw old maps of the island, its coast flecked with Nicobarese villages, all of them gone now, their residents — Nicobarese tribals — now in government colonies closer to Campbell Bay.

It was an indelible trip. One marvelled at how much GNI’s people have lived through. One marvelled too at the endemic biodiversity but feared for the future as well — not just because of logging but also because the airport at Great Nic will almost certainly result in trafficking of locally endemic species. One primary objective got fulfilled. I caught a glimpse of how the earth was before Homo Sapiens began reshaping it. And I saw how GNI itself was, before the port project reduces it into a resource frontier.

In all this, one image stays with me. A macaque sitting in a tree near Galathea, with an unknown future ahead of it. I will leave you with it.

PS: The earth before modern man. Which is why one reads epics like Meghadootam or Jan Vansina’s Paths in the Rainforest. Or, harking farther back into pre-human times, about trilobites, dinosaurs, ancient forests, and the great flowering of biodiversity on this planet. As the concluding paragraph in The Origin Of Species says: “There is grandeur in this view of life… that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

If only we had the morality to see all these lifeforms as our equals — and with an equivalent claim to this planet.

Leave a comment